Allocation is the cornerstone of fishery management, yet it’s seldom discussed plainly in terms of “who gets what.”

Popular species of wild fish are typically shared by three major “user groups”: Private recreational fishermen, who catch fish for their own use; for-hire fishermen, who are paid to take recreational anglers fishing; and commercial fishermen, who harvest fish that are marketed to seafood consumers.

Ideally, managers quantify the volume of fish that can safely be removed from the system and allocate a fixed share of that harvest to each of the three sectors.

The State of Maryland did just that with its striped bass.

STRIPED BASS

In the 1970s and 1980s, under-regulated sport and commercial fishermen depleted stripers along the Atlantic Coast. In an unusually frank assessment, Peter Jensen, who was at the time the Director of Fisheries at Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources, said, “Overfishing is to be blamed on all of us—the recreational and commercial fishermen who did it, and the managers who let it happen.”

To stem the decline, the federal government called a time out. By 1990, the striper population had rebuilt sufficiently to again allow some fishing. As East Coast states reopened their fisheries, recreationists pressured regulators to bar the door to seafood providers.

Some buckled. In New Jersey, the state legislature declared the species a gamefish, off limits to commercial fishermen and consumers. Allocation ratio? 100% to zero.

In Maryland—where most East Coast striped bass are spawned—regulators split the annual allowable catch equitably, with half to the commercial sector and half to the recreational. Then, to accommodate the for-hire charter fleet, managers deducted 7.5 percent from each of the two sectors to end up with a fixed allocation ratio between the three industries of 42.5%:42.5%:15 %.

The Maryland Model has held up for nearly three decades and during that time it’s prevented a lot of arguing. Nothing is static in fisheries, however. Seafood producers can lose out, even with a carved-in-stone allocation scenario in place.

That’s what happened in the Gulf of Mexico where the warm climate and protected waters appear to be breeding recreational anglers like mosquitoes.

SPANISH MACKEREL

The Spanish mackerel likes it toasty and seeks out the gulf’s warmer waters as the seasons change. Because it’s a “highly migratory” species, it’s managed by the federal government.

In the late 1980s, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council recognized that the mackerel was being overfished by under-regulated sport and commercial fishermen.

The panel developed a management plan in response—the plan didn’t shut down any of the fisheries but it did include restrictions that reduced their catches to a level that would allow the mackerel population to rebuild.

Federal managers set an initial gulf-wide quota of 2.5 million pounds, which they allocated to the two sectors according to their historical landings. Since the commercial industry had historically landed about 57 percent of the total catch, it was permitted to harvest up to 1.4 million pounds, while the recreational industry could take up to 1.1 million pounds, about 43 percent of the total.

As the Spanish mackerel population rebuilt, the total allowable catch was increased incrementally until 1999 when it reached the current total of 9.1 million pounds.

With the targeted allocation ratio between the sectors unchanged, the commercial industry’s 57-percent share allowed nearly 5.2 million pounds of mackerel to be caught and distributed to the public, while the 43-percent recreational allocation permitted anglers to bring in nearly 4 million pounds for themselves.

Yet, from 2000 through 2016, when the total annual harvest by the two sectors averaged about 8.3 million pounds, commercial fishermen landed an average of just over 1.3 million pounds per year, about 14 percent of the 9.1-million-pound Total Allowable Catch. Recreational landings—including a 2013 record of 12 million pounds—averaged nearly 7 million pounds per year, about 77 percent of the TAC.¹

So, from a projected allocation scenario of 57% commercial:43% sport, the actual ratio of fish caught is currently about 14%:77%.²

How could this be?

MORE RODS AND REELS, FEWER NETS

As Spanish mackerel migrate back and forth across the gulf, they tend to remain within inshore state waters. (State waters off Texas and the West Coast of Florida extend 9 miles; those off the three central-gulf states reach out 3 miles.)

The federal Gulf Council established a uniform daily recreational bag limit of 15 mackerel for all five gulf states. But there is no limit on the number of recreational fishermen, and as all New Moon Press readers know, the number of sport fishermen began to shoot through the roof in the 1960s as the baby boomers came of age.

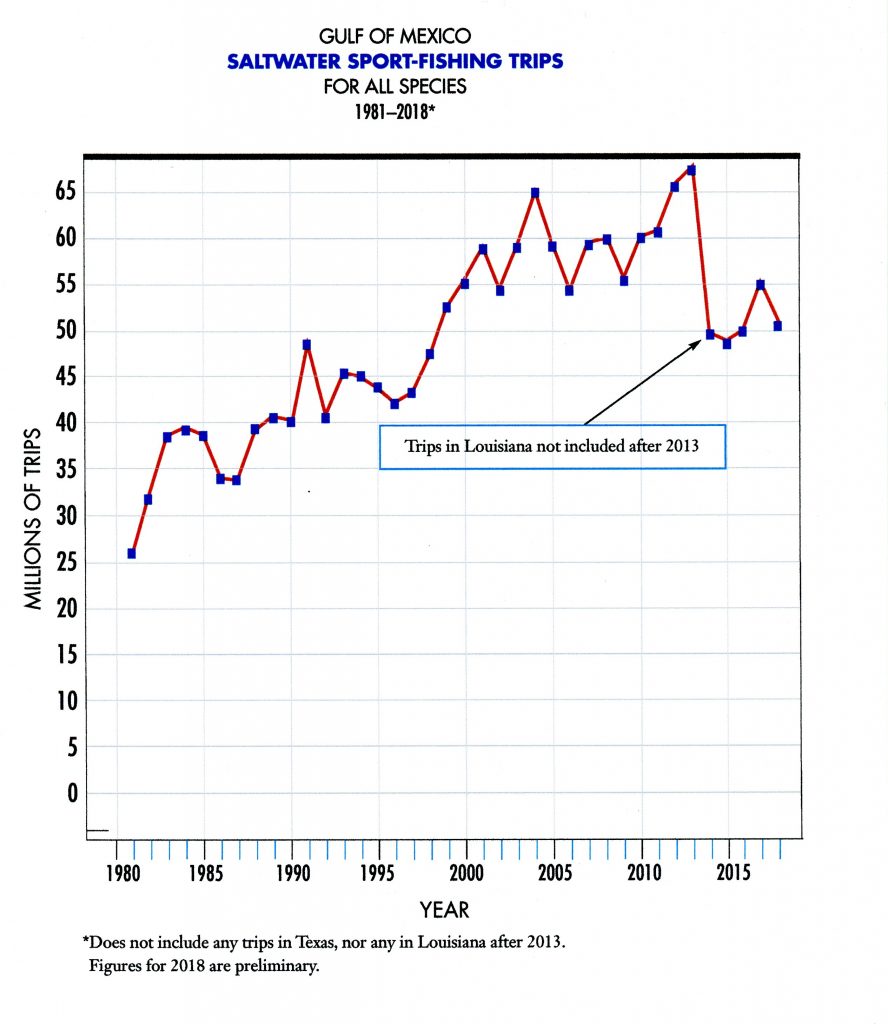

The National Marine Fisheries Service didn’t really try to track the number of recreational anglers until the early 1980s; the graph below illustrates how the number of saltwater sport-fishing trips has trended since then:

NET DERANGEMENT SYNDROME

NET DERANGEMENT SYNDROME

Obviously, more sport-fishing trips equates to more fish being caught by recreational fishermen. But at the same time the sport fishery was expanding, its leaders were pressuring state fishery managers to reduce the catches of commercial fishermen by disallowing the use of their traditional harvesting equipment.

Commercial fishermen harvest shallow-water species like mackerel primarily with gill nets and seines. Texas outlawed the use of those nets in 1988; sportsmen convinced Florida voters to outlaw the use of nets in 1994, and Louisiana and Mississippi soon followed.

During the mid-1990s contagion, Alabama’s managers took the high road, and netters there continue to sustainably harvest up to a million pounds of Spanish mackerel per year. In 2008, however, sport fishermen circumvented the state’s fact-based fishery management system, and convinced state legislators to phase out the net fishery.³

Of the 1.3 million pounds landed commercially across the gulf, Alabama’s net fishermen contributed nearly 1 million pounds per year. As they go out of business, we can anticipate a decline in gulf-wide commercial landings to less than 500,000 pounds, most of which are netted by a couple South Florida boats in federal waters, where management is less capricious than in the states.

From the initial allocation target of 57 percent commercial:43 percent recreational, the recreational sector is on track to win at least 95 percent of the allocation while the commercial sector, with luck, could end up with as much as 5 percent of the catch.

In the Gulf of Mexico that’s nothing new.

¹Recreational catches were in fact considerably greater than reported here because these figures do not include any landings by anglers in Texas; nor are landings from Louisiana included after 2013.

²Percentages don’t add up to 100 because the average annual landings totaled less than the 9.1-million-pound TAC.

³As documented in “A Different Breed of Cat,” slated for release by New Moon Press in late summer, 2019.

DO IT YOURSELF

The landings and trip-related data cited in this article are provided by the federal National Marine Fisheries Service. You paid for this information and you can directly access it.

Simply go to “Links” and scroll down to the two last entries: One is for commercial information and one is for recreational information. Click on either entry and you’ll find yourself on the NMFS website. It can be a little tricky at first, and the agency has a prompt for “First Time Users.” If you still need help, you can seek assistance from an extension fisheries agent via SeaGrant. Or simply email me at robertf@newmoonpress.com and I’ll walk you through the process. Once you know how, it’s easy.