Too much food in America, man. We got so much food in America we’re allergic to food. —Chris Rock, comedian

c as such. When they are, recreational advocates reflexively bring up money i.e. “We should have more of the resource because anglers spend more on their sport than commercial fishermen earn by selling fish for food.

Repeated enough times, this apples-to-oranges argument can eclipse the opinion held by actual economists: They say that the value of a fishery is maximized when it’s shared in a meaningful way between the sport and commercial fisheries.*

But timing is everything, and at a time when “consumers” of goods and services are driving three-fourths of the nation’s economy, “producers” are just in the way.

VROOM

When recreational industry advocates claim that sport fishermen spend more on the consumption of stuff than commercial fishermen earn by producing food, they’re right.

Anglers, before they even go fishing, gear up with boats, motors, trailers, fishing tackle, electronics, apparel and other items. Then, when they go fishing, their trip-related expenses include food and drink, bait, odds and ends like ice and sun-tan lotion, and fuel.

The single greatest recurring expense in fishing is fuel.

Some anglers are content to sit on a bucket by the beach or cast from self-propelled vessels like kayaks; others have even transitioned to electric motors, which are becoming more efficient and less expensive. But in the foreseeable future, most saltwater sportsmen will continue to power their boats with outboard or inboard engines fueled by non-renewable petroleum products.

[Vroom, vroom. Photo of sport boat with three big outboards goes right here]

EFFICIENCY BAD

Commercial fishermen also burn plenty of fuel. Fishing is their work so, on an individual basis, they naturally make a lot more trips in a year than your average recreational fisherman. On the other hand, seafood producers are vastly outnumbered by recreational anglers, and in terms of fuel consumption per fish landed, they’re way more efficient. The trouble is, when you’re trying to maximize consumption, efficiency’s not a good thing.

Let’s allocate 100 fish to each of the industries and see how they compare.

Since commercial fishermen basically live with the fish, the engine in their truck barely has time to warm up before they arrive at the dock where their boat is tied up. So, fuel consumption related to travel? Negligible.

Contrary to popular perception, commercial fishermen may not always catch a hundred fish in a day, even with nets. But let’s assume that this one does, after cruising most of the day in search of fish schools large enough to warrant roping up in her net. Fuel consumption related to the harvest of 100 fish? Twenty gallons of gasoline, .2 gallons per fish.

The fish house, after purchasing this net fisherman’s catch, packs her fish along with those of its other fishermen, then trucks them all from the coast to the nearest urban distributor. If the fish house’s vehicle carries 1,000 fish and consumes 20 gallons of diesel on the round trip to and from the city, its delivery-related fuel consumption is .02 gallons per fish, or 2 gallons total for our original 100 fish.

Urban distributors process whole fish by filleting. An average fish yields about one-third by weight of boneless meat, so let’s assume that our 100 fish are all 6-pound redfish (keeping in mind that politicians in most Gulf Coast states have allocated all of our wild red drum to recreational anglers). The processor thus transforms 100 whole, 6-pound fish into 200 boneless fillets, each weighing one pound—a substantial-sized serving—and then distributes them to local markets and restaurants.

Inner city delivery trucks are nimble, the distances aren’t far, so a nominal amount of fossil fuel is consumed. Still, let’s be liberal and say the driver burnt 10 gallons delivering the 200 meals that were derived from the original 100 fish, or .1 gallons per fish.

In total then, producers burnt 20 gallons of gas harvesting the fish, 2 gallons of diesel delivering them to the city, and another 10 gallons delivering them to the retail outlets—32 gallons.

Let’s round that up to 35 gallons, which is the total fossil fuel that was consumed by the commercial sector in making 100 wild fish available to at least 200 consumers—a maximum of about one-third of a gallon per fish.

INEFFICIENCY GOOD

Now let’s allocate 100 redfish to the recreational sector.

Like commercial fishermen, some recreational anglers also reside in the vicinity of the fish and so don’t have to travel very far to get after them. Most, however, journey to the coast from elsewhere.

If driving—as opposed to jetting in from a distant state or country—the angler might tank up his SUV or pickup truck with, say, 15 gallons of gasoline; while at the pump, he may also top off the tank on his boat with an additional 25 gallons.

The sport is called “fishing,” not “catching,” so the intrepid angler may go home empty handed. But we’ll assume that he catches his limit, which in Louisiana is currently five redfish per day.

If he burns all of his fuel by the time he gets back home, he will have consumed 40 gallons of gas to bag 5 red drum—8 gallons per fish.

Because Bayou State anglers are restricted to just 5 reds per day, it would require a minimum of 20 trips to legally catch the same 100 that our comely netter wrapped up in one. Assuming that anglers consistently burnt 40 gallons of gas on each of those trips, they would consume a total of 800 gallons. That’s 40 times—or 4,000 percent—more than the 20 gallons our net fishermen used to harvest the same number of fish.

Recreational angling becomes even less efficient when bag limits are reduced.

In parts of Florida’s Gulf Coast, the daily bag limit of red drum is just one fish. So, it would take recreational anglers 100 successful trips to legally catch 100 redfish. Assuming, again, that anglers consume 40 gallons per trip, they’d now burn at least 4,000 gallons of petroleum to obtain 100 fish, 200 times—or 20,000 percent—more than the amount consumed by our nettress.

Zero bag limits, when no fish are retained, are of course the least efficient of all.

Some species of fish, like bonefish and tarpon, are so “game” that anglers wouldn’t consider keeping them for dinner. “Catch and release” fishing is as inefficient as you can get, but when you’re trying to maximize the consumption of everything but fish it doesn’t get any better.

ONLY IN AMERICA

The industry-to-industry comparisons above are clearly conservative, on the recreational side, because they assume that every sport-fishing trip was 100 percent successful, and that the anglers consumed only moderate amounts of fuel in medium-sized engines. Bigger engines and unsuccessful trips reduce efficiency, in terms of fuel consumption per fish landed.

If we disregarded efficiency and simply compared the overall fuel consumption by the two industries, we’d find that the amount consumed by a handful of commercial fishermen is a drop in the bucket compared to the amount consumed by hundreds of thousands of recreational fishermen.

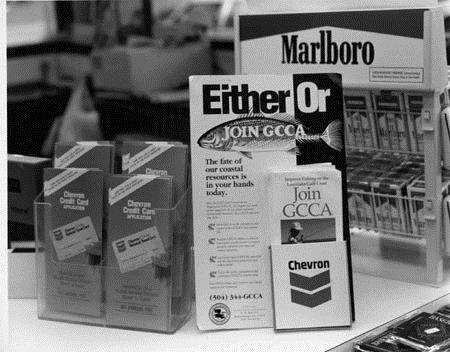

That’s one of the reasons that oil companies are so eager to support “conservation” groups that lobby for subtracting fish from the pesky commercial sector and adding them to the recreational.

Only in America.

*One example: An Economics Guide to Allocation of Fish Stocks between Commercial and Recreational Fisheries. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS 94, November 1990. https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/spo/SPO/tr94opt.pdf

Chevron is just one of many corporate supporters of the recreational industry’s Coastal Conservation Association, a national group whose members consider it to be “conservation” when they’re catching all the fish.